Introducing the Rational Speech Act framework

Chapter 1: Language understanding as Bayesian inference

A: “Can you pass the salt?” B: [passes the salt]

A’s utterance functions here as an indirect request, not a literal information-seeking question about B’s physical ability to pass the salt. But how did B know that? Following refp:grice1969utterer, we might begin with the distinction between the sentence meaning (the truth conditions attached to these words composed in this sequence) and the speaker meaning (what A intended to communicate by uttering that sentence in a particular context). Formal semantics has developed rigorous tools for understanding the former. But the latter has often been consigned to the “wastebasket” refp:bar1971out, depending on innumerable contextual factors too hopelessly complex to sort out.

Recently, the field of formal pragmatics has begun to systematize how we go from literal meanings of words and their compositional combination — the domain of semantics — to what speakers actually communicate in context. The key insight is that pragmatic inference isn’t random or unprincipled. When B interprets “Can you pass the salt?” as a request, they’re following a systematic reasoning process: they recognize that A probably already knows B is physically capable of passing salt, so the literal question interpretation would be pointless. Instead, B reasons about what A might be trying to achieve by producing this utterance.

The Rational Speech Act (RSA) framework refp:frankgoodman2012 captures this reasoning using tools from probability and decision theory. It treats communication as a kind of recursive social reasoning: speakers choose utterances by thinking about how listeners will interpret them, while listeners interpret utterances by thinking about why speakers chose them. The resulting interpretation necessarily depends on the literal interpretation of an utterance, but is not wholly determined by it, offering an explanation for complex phenomena ranging from metaphor refp:kaoetal2014metaphor and hyperbole refp:kaoetal2014 to vagueness in degree semantics refp:lassitergoodman2013.

In this chapter, we’ll build up a simple RSA model step by step, starting with a basic scenario where speakers need to identify objects for listeners. While this “reference game” might seem far removed from the subtle pragmatics of indirect requests or conversational implicature, it contains all the essential ingredients of pragmatic reasoning. Once we understand how the framework operates in this simple case, we’ll be prepared to extend it to increasingly complex phenomena in the chapters that follow.

Introducing the Rational Speech Act framework

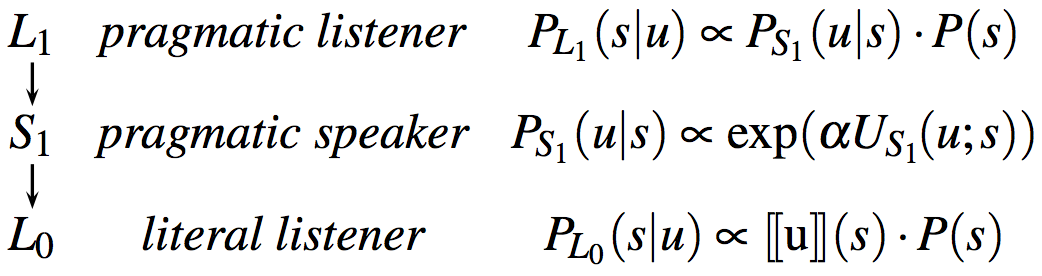

The Rational Speech Act (RSA) framework views communication as recursive reasoning between a speaker and a listener. The listener interprets the speaker’s utterance by reasoning about a cooperative speaker trying to inform a naive listener about some state of affairs. Using Bayesian inference, the listener reasons about what the state of the world is likely to be given that a speaker produced some utterance, knowing that the speaker is reasoning about how a listener is most likely to interpret that utterance. Thus, we have (at least) three levels of inference. At the top, the sophisticated, pragmatic listener, \(L_{1}\), reasons about the pragmatic speaker, \(S_{1}\), and infers the state of the world given that the speaker chose to produce the utterance \(u\). The speaker chooses \(u\) by maximizing the probability that a naive, literal listener, \(L_{0}\), would correctly infer the state of the world given the literal meaning of \(u\).

To make this abstract architecture more intelligible, let’s consider a concrete example for a “vanilla” RSA model. In its initial formulation, reft:frankgoodman2012 modeled referent choice in efficient communication. Let’s suppose that there are only three objects that the speaker and listener want to talk about, as in Fig. 1.

In a reference game, a speaker wants to refer to one of the given objects. To simplify, we assume that the speaker may only choose one property (see below) with which to do so. In the example of Fig. 1, the set of objects

\[O = \{\text{blue-square}, \text{blue-circle}, \text{green-square}\}\]contains the three objects given. The set of utterances

\[U = \{ \text{"square"}, \text{"circle"}, \text{"green"}, \text{"blue"} \}\]contains the four properties from which the speaker can choose.

A vanilla RSA model for this scenario consists of three recursively layered, conditional probability rules for speaker production and listener interpretation. These rules are summarized in Fig. 2 and will be examined one-by-one below. The overal idea is that a pragmatic speaker \(S_{1}\) chooses a word \(u\) to best signal an object \(o\) to a literal listener \(L_{0}\), who interprets \(u\) as true and finds the objects that are compatible with the meaning of \(u\). The pragmatic listener \(L_{1}\) reasons about the speaker’s reasoning and interprets \(u\) accordingly, using Bayes’ rule; \(L_1\) also weighs in the prior probability of objects in the scenario (i.e., an object’s salience, \(P(o)\)). By formalizing the contributions of salience and efficiency, the RSA framework provides an information-theoretic definition of informativeness in pragmatic inference.

The literal listener

At the base of this reasoning, the naive, literal listener \(L_{0}\) interprets an utterance according to its meaning. That is, \(L_{0}\) computes the probability of \(o\) given \(u\) according to the semantics of \(u\) and the prior probability of \(o\). A standard view of the semantic content of an utterance suffices: a mapping from states of the world to truth values. For example, the utterance \(\text{"blue"}\) is true of states \(\text{blue-square}\) and \(\text{blue-circle}\) and false of state \(\text{green-square}\). We write \([\![u]\!] \colon O \mapsto \{0,1\}\) for the denotation function of this standard, Boolean semantics of utterances in terms of states. The literal listener is then defined via a function \(P_{L_{0}} \colon U \mapsto \Delta^S\) that maps each utterance to a probability distribution over world states, like so:

\[P_{L_{0}}(o\mid u) \propto [\![u]\!](o) \cdot P(o)\]Here, \(P(o)\) is an a priori belief regarding which state or object the speaker is likely to refer to in general. These prior beliefs can capture general world knowledge, perceptual salience, or other things. For the time being, we assume a flat prior belief according to which each object is equally likely. (As we move away from flat priors, we’ll want to revise these assumptions so that \(L_0\) (but not \(L_1\)!) uses a uniform prior over states. In fact, this is what reft:frankgoodman2012 assumed in their model. )

This literal listener equation can be implemented as follows in memo (see Appendix Chapter 1 for a basic tutorial on memo syntax):

from memo import memo

import jax

import jax.numpy as np

from enum import IntEnum

# Define the objects and utterances using simple IntEnum

class Object(IntEnum):

BLUE_SQUARE = 0

BLUE_CIRCLE = 1

GREEN_SQUARE = 2

class Utterance(IntEnum):

BLUE = 0

GREEN = 1

SQUARE = 2

CIRCLE = 3

# Denotation function: which of these utterances are true of which objects?

@jax.jit

def meaning(utterance, obj):

return np.array([

[True, True, False], # BLUE: true for the blue objects

[False, False, True ], # GREEN: true for the green objects

[True, False, True ], # SQUARE: true for the square objects

[False, True, False] # CIRCLE: true for the circle objects

])[utterance, obj]

@memo

def L0[_u: Utterance, _o: Object]():

listener: knows(_u)

listener: chooses(o in Object, wpp=meaning(_u, o))

return Pr[listener.o == _o]

def test_literal_listener(utterance):

print(f"Literal listener interpretation of '{utterance.name}':")

outcomes = L0()

for obj in Object:

print(f"P({obj.name} | '{utterance.name}') = {outcomes[utterance][obj]:.3f}")

test_literal_listener(Utterance.BLUE)

Exercises:

- Try testing the literal listener’s behavior with different utterances. What happens when you use

Utterance.SQUAREorUtterance.GREEN?- Add a fourth object (e.g., a green circle) to the scenario. How does this change the literal listener’s behavior?

- In this example, we implicitly imposed a uniform prior over the three objects. Where in the model is this assumption being made? What happens when the listener’s beliefs are not uniform over the possible objects of reference, e.g., the “green square” is very salient? (Hint: think about the

wppterm in thechoosesstatement.)- The denotation function is manually specified as a Boolean matrix for this simple example. Can you make this a function of object properties to make the code more easily maintainable for different sets of utterances and objects? Note that we’re under some strict constraints from JAX here: for the code to compile and run fast, we need to operate with arrays.

Fantastic! We now have a way of specifying how a listener will interpret the truth functional meaning of a referential utterance in a given context of objects. Let’s unpack some of the memo syntax.

-

The

knowsstatement explicitly establishes that the listener agent has certain information available to them. In this case, we assume the listener heard an utterance_uso they can use it in their reasoning. What happens when we remove this line? -

The

choosesstatement represents the listener making a choice among options. Here, the listener is choosing an object o from the set of possible Objects. Thewppparameter stands for “with probability proportional to” - it determines the probability weights for each choice. In this case,wpp=meaning(_u, o)means the probability of choosing object o is proportional to whether the (known) utterance _u is true of that object, as determined by the meaning function. This implements the literal semantics. -

The return statement

Pr[listener.o == _o]says that we want the probability that the listener’s chosen object o equals the specific object _o that we’re querying about. ThePr[...]syntax asks “what is the marginal probability that this condition is true?”

The pragmatic speaker

One of Grice’s core insights was that linguistic utterances are intentional actions. Thus, we model the speaker as a rational (Bayesian) actor. They choose an action (e.g., an utterance) according to its utility. Rationality is often defined as choosing an action that maximizes the agent’s (expected) utility. Here, we consider a generalization in which speakers use a softmax function to approximate the (classical) rational choice. (For more on the properties of the softmax funciton, see this nice tutorial.)

In the code box below, you’ll see a generic approximately rational agent model.

In memo, we use factor statements to increment log-probabilities, which effectively implements softmax decision-making. Each factor statement adds to the log-score of the current execution path, and memo normalizes these to compute probabilities. In effect, the function agent computes the distribution:

# Define possible actions

class Action(IntEnum):

A1 = 0

A2 = 1

A3 = 2

# Define utilities for the actions

@jax.jit

def utility(action):

return np.array([0, 1, 2])[action]

# Define a rational agent who chooses actions according

# to their expected utility

@memo

def agent[_a: Action](alpha):

speaker: chooses(a in Action, wpp=exp(alpha * utility(a)))

return Pr[speaker.a == _a]

# Test the agent

print("Probability that an agent will take various actions:")

agent(1, print_table=True)

Exercises:

- Explore what happens when you change the actor’s optimality parameter

alpha. What doesalpha = 0represent? What happens asalphaapproaches infinity?- Explore what happens when you change the utilities in the

utility()function to [4,5,6]? (Hint: think about what matters for the softmax – absolute values or relative differences?). What if all utilities are equal?- Add a fourth action

A4with utility 10. How does the probability distribution change?

In language understanding, the utility of an utterance is how well it communicates the state of the world \(s\) to a listener. So, the speaker \(S_{1}\) chooses utterances \(u\) to communicate the state \(s\) to the hypothesized literal listener \(L_{0}\). Another way to think about this: \(S_{1}\) wants to minimize the effort \(L_{0}\) would need to arrive at \(s\) from \(u\), all while being efficient at communicating. \(S_{1}\) thus seeks to minimize the surprisal of \(s\) given \(u\) for the literal listener \(L_{0}\), while bearing in mind the utterance cost, \(C(u)\). (This trade-off between efficacy and efficiency is not trivial: speakers could always use minimal ambiguity, but unambiguous utterances tend toward the unwieldy, and, very often, unnecessary. We will see this tension play out later in the book.)

Speakers act in accordance with the speaker’s utility function \(U_{S_{1}}\): utterances are more useful at communicating about some state as surprisal and utterance cost decrease. (See the Appendix Chapter 2 for more on speaker utilities.)

\[U_{S_{1}}(u; s) = \log L_{0}(s\mid u) - C(u)\](In memo, we can access \(\log L_{0}(s\mid u)\) through the literal listener’s output probabilities.)

Exercise: Return to the first code box and find \(\log L_{0}(s\mid u)\) for the utterance “blue” and each of the three possible reference objects.

With this utility function in mind, \(S_{1}\) computes the probability of an utterance \(u\) given some state \(s\) in proportion to the speaker’s utility function \(U_{S_{1}}\). The term \(\alpha > 0\) controls the speaker’s optimality, that is, the speaker’s rationality in choosing utterances. We define:

\[P_{S_{1}}(u\mid s) \propto \exp(\alpha U_{S_{1}}(u; s))\,,\]which expands to:

\[P_{S_1}(u \mid s) \propto \exp(\alpha (\log L_{0}(s\mid u) - C(u)))\,.\]The following code implements this model of the speaker. In the following code, we assume that all utterances are equally costly (i.e., \(C(u) = C(u')\) for all \(u, u'\)) (see Appendix Chapter 3 for more on message costs and how to implement them).

@memo

def S1[_u: Utterance, _o: Object](alpha):

speaker: knows(_o)

speaker: chooses(u in Utterance, wpp=exp(alpha * log(L0[u, _o]())))

return Pr[speaker.u == _u]

def test_pragmatic_speaker(alpha, obj):

print(f"Literal listener interpretation of '{obj.name}':")

outcomes = S1(alpha)

for utterance in Utterance:

print(f"P('{utterance.name}' | {obj.name}) = {outcomes[utterance][obj]}")

test_pragmatic_speaker(1, Object.GREEN_SQUARE)

Exercise: Check the speaker’s behavior for different objects. What happens when you test with

Object.GREEN_SQUAREorObject.BLUE_CIRCLE? How does changing thealphaparameter affect the speaker’s behavior?

We now have a model of the utterance generation process. With this in hand, we can imagine a listener who thinks about this kind of speaker.

The pragmatic listener

The pragmatic listener \(L_{1}\) computes the probability of a state \(s\) given some utterance \(u\). By reasoning about the speaker \(S_{1}\), this probability is proportional to the probability that \(S_{1}\) would choose to utter \(u\) to communicate about the state \(s\), together with the prior probability of \(s\) itself. In other words, to interpret an utterance, the pragmatic listener considers the process that generated the utterance in the first place. (Note that the listener model uses observe, which functions like factor with \(\alpha\) set to \(1\).)

@memo

def L1[_u: Utterance, _o: Object](alpha):

listener: knows(_u)

listener: chooses(o in Object, wpp = S1[_u, o](alpha))

return Pr[listener.o == _o]

def test_pragmatic_listener(utterance, alpha=1.0):

print(f"Pragmatic listener interpretation of '{utterance.name}' (alpha={alpha}):")

outcomes = L1(alpha)

for obj in Object:

print(f"P({obj.name} | '{utterance.name}') = {outcomes[utterance][obj]:.3f}")

test_pragmatic_listener(Utterance.BLUE)

Putting it all together

So far, we’ve implemented the RSA framework by defining separate functions for each level of reasoning: L0 for literal listeners, S1 for pragmatic speakers, and L1 for pragmatic listeners. While this approach works and gives us the correct results, it doesn’t leverage the full power of memo, which makes the recursive reasoning structure more transparent.

We can combine all these pieces into a single function.

@memo

def L[u: Utterance, o: Object](alpha):

listener: thinks[

speaker: chooses(o in Object, wpp=1),

speaker: chooses(u in Utterance, wpp=imagine[

listener: knows(u),

listener: chooses(o in Object, wpp=meaning(u, o)),

exp(alpha * log(Pr[listener.o == o]))

])

]

listener: observes [speaker.u] is u

listener: chooses(o in Object, wpp=Pr[speaker.o == o])

return Pr[listener.o == o]

def test_pragmatic_listener(utterance, alpha=1.0):

print(f"Listener interpretation of '{utterance.name}' (alpha={alpha}:")

outcomes = L(alpha)

for obj in Object:

print(f"P({obj.name} | '{utterance.name}') = {outcomes[utterance][obj]:.3f}")

test_pragmatic_listener(Utterance.BLUE)

Exercises:

- Explore what happens if you increase the

alphasoftmax temperature parameter. What happens when you set alpha=0?memoprovides a helpful INSPECT() function to print out what an agent knows at different points in the code. Try inserting the linelistener: INSPECT()before and after theobservesstatement. What did theobservesstatement change about the listener’s state?- Try adding a new multi-word utterance (e.g., “blue square”). What should its meaning be?

- Add a simple cost function where longer utterances (like “blue square”) are more costly than shorter ones (like “blue”). How does this affect the speaker’s choices?

- Can you implement higher levels of recursion? When does the model converge? How does the alpha parameter interact with the recursion level?

In the next chapter, we’ll move beyond simple reference games to see how RSA models have been developed to model more complex aspects of pragmatic reasoning and language understanding.

Table of Contents